Did Roman Poet Virgil Prophesy the Birth of Christ?

The Roman Poet Virgil (70 – 19BC), writer of the Epic Poem The Aeneid, also wrote of the birth of a child who would usher in a golden age of peace.

The reference to the child is contained in the Fourth Eclogue, written about 40BC. It is dedicated to his friend the consul Pollio. In later centuries, subsequent Christians would see it as Virgil’s prophesying the coming of Christ.

The Eclogues meaning “choice” or “selection” from the Greek eclogue, are pastoral poems whose subject are shepherds and their flocks and the easy charm of the rustic countryside. They celebrate an idealised pastoral paradise of simple living associated with Arcadia and the reign of Saturn in Roman Myth (Cronos in Greek).

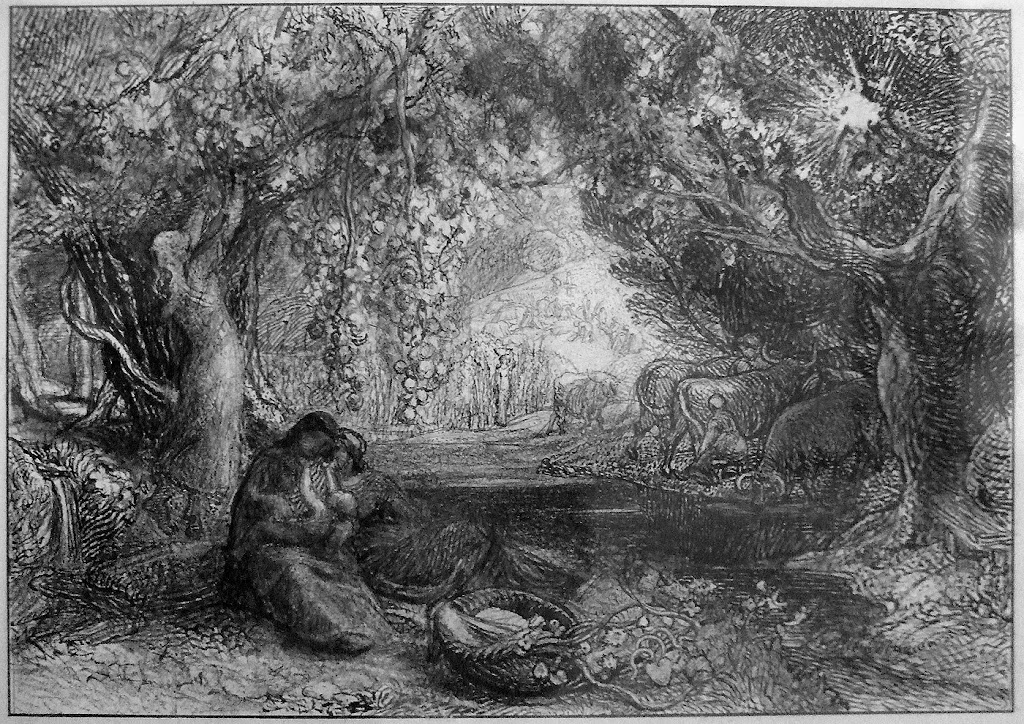

|

| Ages of Man – The Golden Age by Lucas Cranach the Elder (Source: Wikipedia) |

The Dawn of a New Age

The poem begins by invoking the Muses, and refers to the dawning of a new age. It makes specific reference to the Sybil of Cumae, the return of Justice and the reign of Saturn and the arrival of a new kind of men sent down from heaven. The idea of the Ages of Man, which is first explored by Hesiod in his Theogony, refers to The Golden Age of Man during the reign of Cronos (Roman Saturn). This was an age when men lived long peaceful lives without toil or strife, similar to that of Saturn in Roman Myth.

“Now the last age by Cumae’s Sibyl sung

Has come and gone, and the majestic roll

Of circling centuries begins anew:

Justice returns, returns old Saturn’s reign,

With a new breed of men sent down from heaven.”

The Birth of a Divine Child

The poem continues and says a boy will be born who will usher in a golden age when the present iron age shall cease and the earth be freed from ‘never-ceasing fear’. When is this new age to occur? It says during the consulate of Pollio, Virgil’s friend.

It has been said by scholars that the mysterious child refers to the expected child of Antony and Octavia, however, Virgil does not say who the child is. Although it most likely refers to a prospective child from the aforementioned union, it does make curious references about the birth of a divine child sent down from heaven who will bring peace to the world. It is easy to see why later Christians took it as prophesying the coming of Christ.

“Only do thou, at the boy’s birth in whom

The iron shall cease, the golden race arise,

Befriend him, chaste Lucina; ’tis thine own

Apollo reigns. And in thy consulate,

This glorious age, O Pollio, shall begin,

And the months enter on their mighty march.

Under thy guidance, whatso tracks remain

Of our old wickedness, once done away,

Shall free the earth from never-ceasing fear.

He shall receive the life of gods, and see

Heroes with gods commingling, and himself

Be seen of them, and with his father’s worth

Reign o’er a world at peace.”

The Decree of Destiny?

Virgil towards the end of the poem invokes the decree of the Fates and Destiny and says this time is fast approaching. The earth, sea and starry heavens all seem to be passionately expecting this coming time.

“”Such still, such ages weave ye, as ye run,”

Sang to their spindles the consenting Fates

By Destiny’s unalterable decree.

Assume thy greatness, for the time draws nigh,

Dear child of gods, great progeny of Jove!

See how it totters- the world’s orbed might,

Earth, and wide ocean, and the vault profound,

All, see, enraptured of the coming time!”

Whether Virgil is speaking of the birth of Antony and Octavia’s child to be or some other unknown child, we do not know. Possibly he doesn’t know either. Also the consulate of Pollio begins about 40 years before the birth of Christ. But I suppose 40 years in the long measure of great ages is but a blip in time.

Regardless, it does appear to foretell the birth of a divine child who will bring peace to the world. Although this is unlikely given he was not Christian, it is tempting to think that maybe, just maybe, Virgil was tapping into the muses and revealing destiny’s hidden decree.

Sources:

https://www.britannica.com/art/eclogue

http://classics.mit.edu/Virgil/eclogue.4.iv.html

https://www.encyclopedia.com/arts/culture-magazines/eclogues

https://www.worldhistory.org/Saturn/