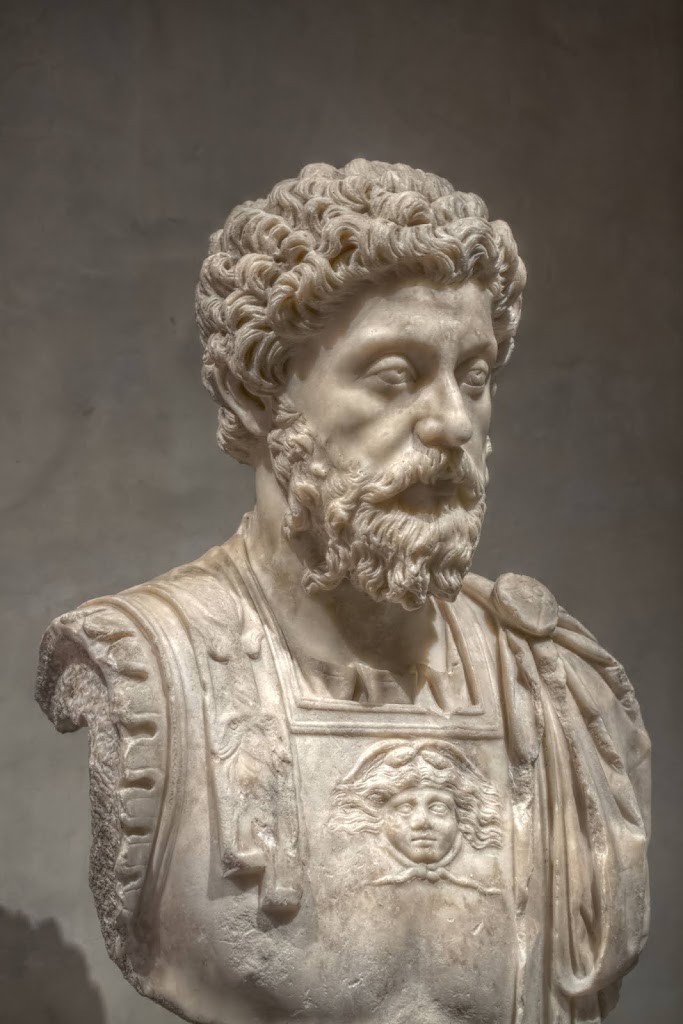

Marcus Aurelius on How to Secure an Everlasting Spring

Marcus Aurelius (AD 121-180), was an interesting historical figure in more ways than one. His Meditations provide a unique window into the soul of one of the world’s most powerful people and a philosopher striving to live virtuously in the tumult of his age. Many of the passages he wrote to himself deal with everyday concerns and problems that we would today recognise.

The Metaphor of a Spring and Apatheia

In a passage in Book 8 of the Meditations, he reflects on the ‘curses’ likely in the imperial court, asking himself how he can maintain his calm and secure an everlasting spring in the midst of such conditions.

He writes the following:

‘They kill, they cut to pieces, they hunt with curses’. What relevance has this to keeping your mind pure, sane, sober, just? As if a man were to come up to a spring of clear, sweet water and curse it — it would still continue to bubble up water good to drink.

(Meditations, p.81, 51 )

Above he used the metaphor of a spring and compared his mind to a spring, which despite the abuse and words hurled at it, nevertheless remains unaffected, clear and pure. He recognised that such abuse and threats, though unpleasant, are external and thus out of his control. Furthermore they cannot affect his internal state of mind, which despite the abuse hurled at it, maintained the clear purity of a spring.

As he further relates:

He could throw in mud or dung: in no time the spring will break it down, wash it away, and take no colour from it.

(Meditations, p. 81)

Like the spring his mind was undisturbed by any abuse or threats from without. This is known in Stoicism as Apatheia “without pathos”. Not to be confused with the modern english ‘apathy’, it was a state of mind free from emotional disturbances and passions, such as fear, desire and pleasure.

The Four Passions and the Dichotomy of Control

In Stoicism these were known as the four passions: lupe, phobos, epithumia and hedone. Lupe was emotional distress at a current situation considered bad. Phobos was fear of a future event or object that was not present. Epithumia was a desire towards a future something considered to be good and Hedoni, an impulse towards a present thing thought to be good. To free oneself from such passions was no easy thing to do, but for the early Stoic’s, a possibility for the Sage.

But how was one to be free of these passions and achieve the peace of mind of the Sage?

One of the ways was to first recognise what is under our control and what is not. Our mind and our reactions are under our control. The words and opinions of others are not. This is known as the ‘Dichotomy of Control’ in Stoic Philosophy.

But how does this relate to the above passions mentioned?

Take Lupe or distress at a current situation you think is bad. For example, someone says something that insults you and you feel injured or offended. But why should you be upset by it? Is it in your control what other people say or think about you? And are we harmed by the words or by our reaction to the words (being upset), which is under our control?

As is seen from the above example it is not easy and required tremendous self-examination. Even so, Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations are an inspiring example to that end. Below he provides an answer to how he attempted to secure an everlasting spring.

He says:

How then can you secure an everlasting spring and not a cistern? By keeping yourself at all times intent on freedom — and staying kind, simple and decent.

(Meditations, p. 81)

Sources:

Aurelius, M (2006), Meditations. Translated by M. Hammond. Introduction by Diskin Clay. London: UK. Penguin Books