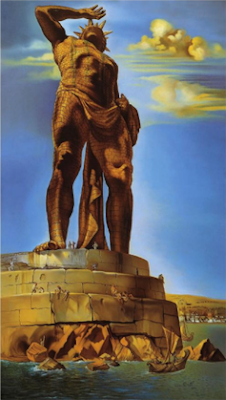

The Colossus of Rhodes: Still a Wonder to Behold?

Nowadays when most of us hear the word, Colossus, it is used as a byword for something or someone — enormous, huge or gigantic. But in the ancient world, there was only one — The Colossus of Rhodes.

The Colossus of Rhodes, a gigantic statue of the sun-god Helios, once stood near the harbour of Rhodes in Greece. Considered one of the Seven Wonders of The Ancient World, it towered over the port of Rhodes for 56 years until it was toppled by an earthquake in 226 BC. There it lay for almost a millennium, its immense limbs still a wonder to behold for passing travellers.

|

| Location of the Island of Rhodes (Source) |

Rhodes is a Greek island located 18 km (11 miles) south west of the coastline of Turkey, in the Eastern Aegean Sea. The island is part of a group of islands known as The Dodecanese. In the 3rd century BC, it was part of the Hellenistic world and the empire established by the Alexander the Great (356-323 BC).

After the death of Alexander, the empire was divided between his generals. In the fighting that ensued, Rhodes aligned itself with Ptolemy I of Egypt. Another general, Antigonus I was annoyed by this and sent his son, Demetrius I Poliorcetes (besieger of cities), to capture the city and island of Rhodes.

With a considerable force of 40,000 soldiers and massive siege engines he laid siege to the city and its walls. But due to a desperate defence and the arrival of a relief force sent by Ptolemy, after 12 months the besieger finally withdrew leaving the massive siege engines behind. According to Pliny the Elder, these siege engines were sold for 300 talents, the sum being used to fund the building of a monument to commemorate the victory.

The Construction of The Colossus

The artist commissioned to create the monument was a sculptor called Chares the Lindian (another city on the island). Construction began in 294BC and would take 12 years to complete. The statue was constructed gradually from the bottom up with large bronze pieces reinforced internally with iron. Massive stones filled the lower portions of the structure to help stabilise it as it rose.

To assist in the gradual stages of construction, earthen ramps were mounted next to the rising structure, to be cleared away when it was finished. When completed, the Colossus stood 70 cubits (105 feet) tall or 32 metres (similar in height to the Statue of Liberty) and rested upon a 50 foot marble base. The towering bronze figure would have reflected the light of the sun, Helios, a bright symbol of Rhodes’ autonomy and independence for all to see.

The base of the statue is said to have been inscribed with these words:

“To you, Helios, yes to you the people of Dorian Rhodes raised this colossus high up to the heaven, after they had calmed the bronze wave of war, and crowned their country with spoils won from the enemy. Not only over the sea but also on land they set up the bright light of unfettered freedom.” (Palatine Anthology, (VI.171))

Still a Wonder to Behold

|

| Engraving of The Colossus by Martin Heemskerck 16th Century. Part of a series depicting the Seven Wonders of the World. (Source: Wikimedia Commons) |

The Colossus of Rhodes was not to remain standing for long. In 226 BC, after 56 years it was toppled by an earthquake. According to the geographer Strabo, it was struck off at the knees where it fell to the ground. Initially there were calls to rebuild the Colossus, however, due to the warning of an oracle – that if it were rebuilt it would imperil the city – the Rhodians refused and consequently, left it to lie where it had fallen.

There it was to remain for centuries, still a wonder to behold for passing travellers. So much so that in the ancient world, it was on a sort of ‘bucket list’ of sights that travellers had to see. It was widely considered by scholars of the time as one of the Seven Wonders of the World, in the company of such illustrious names as The Hanging Gardens of Babylon and the Great Pyramid of Giza.

One of these curious travellers, Pliny the Elder, provides a tantalising account of the wonder The Colossus was still able to evoke, even as it lay broken on the ground two centuries later.

“This statue fifty-six years after it was erected, was thrown down by an earthquake; but even as it lies, it excites our wonder and admiration. Few men can clasp the thumb in their arms, and its fingers are larger than most statues. Where the limbs are broken asunder, vast caverns are seen yawning in the interior.” (Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, BK 34, 18)

What became of The Colossus and How and Where did it stand?

|

| The Colossus of Rhodes with feet and camels depicted (Italy, 1610) (source: Wikimedia Commons) |

For centuries after Pliny the Elder recorded those words, the Colossus remained where it had fallen. However, in the year 654 AD, an Arab force under Muawiyah I captured the island of Rhodes. The Colossus was broken up and sold for scrap. The pieces are said to have been loaded on the backs of 900 camels and transported to Mesopotamia. In the years following this, it was said that pieces of the once-mighty statue were still being found and sold along the caravan route.

In the Medieval and early modern period, the Colossus was remembered as one of the Seven Wonders of the World. It was often incorrectly depicted in illustrations with its feet bestride the entrance to the harbour, and with tall ships passing between its outstretched legs (see the above engraving by Martin Heemskerck).

Even Shakespeare in his play Julius Caesar, has Cassius remark of Caesar:

“Why man, he doth bestride the narrow world

Like a Colossus, and we petty men

Walk under his huge legs and peep about

To find ourselves dishonorable graves” (Julius Caesar, 1.2.135)

Although an apt poetic description of Caesar, there is no evidence in the ancient sources that it stood with one foot either side of the harbour entrance. Nor does it seem architecturally possible considering the known dimensions of the structure. Considering that it is reported to have fallen to the ground, this would seem to indicate that it stood beside the entrance to the harbour, or perhaps further inland, rather than over it.

One site that may have been the location of the statue is the medieval Fortress of Saint Nicholas. Before the fortress was built there existed a church of Saint Nicolas on the site. A medieval tradition said that the enormous feet of the Colossus once occupied the site before the church was built.

Recent evidence appears to corroborate this. A large circle of sandstone blocks have been found that may have been part of the statue’s base, as well as curved marble blocks dating from the 3rd century BC, that appear to have been haphazardly placed into the foundations of the fortress walls.

|

| Saint Nicholas Fortress stands on the opposite side of the entrance to the Harbour (Source: Wikimedia Commons) |

In any case, the mistaken notion that the feet stood bestride the harbour, persisted into modern times. Emma Lazarus, in one of her sonnets, “The New Colossus” (1883), which is mounted on a bronze plaque on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty in New York, contains the lines:

“the brazen giant of Greek fame

with conquering limbs astride from land to land”

In more recent times, there have been calls to rebuild the ancient wonder in Rhodes, but these to date have not eventuated. Many of the most recent proposals for a ‘new Colossus’, depict the structure standing bestride the entrance to the modern harbour, contrary to both ancient and recent scholarly and scientific evidence.

For now at least, the warning of the oracle holds true – The Colossus of Rhodes will not be re-built. And maybe that is for the best. Either way, its ability to make us wonder lives on, as it did for the ancient travellers who beheld its gigantic limbs.

Sources:

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Colossus-of-Rhodes

Cartwright, M. (2018, July 25). Colossus of Rhodes. World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/Colossus_of_Rhodes/

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/colossus

http://www.libertystatepark.com/emma.htm

https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Colossus_of_Rhodes

Ancient Sources:

Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, Book 34.18

Geography, Strabo, Book 14.2.5

https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0099.tlg001.perseus-grc1:14.2.5